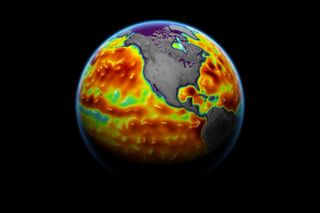

Climate change has already increased the frequency and severity of hurricanes and other extreme weather events around the world. — But there's a smaller, less splashy threat on the horizon that could wreak havoc on America's coasts.

High-tide floods, also called "nuisance floods," occur in coastal areas when tides reach about 2 feet (0.6 meters) above the daily average high tide and begin to flood onto streets or seep through storm drains. True to their nickname, these floods are more of a nuisance than an outright calamity, inundating streets and homes, forcing businesses to close and causing cesspools to overflow — but the longer they last, the more damage they can do.

The U.S. experienced more than 600 of these floods in 2019, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). But now, a new study led by NASA warns that nuisance floods will become a much more frequent occurrence in the U.S. as soon as the 2030s, with a majority of the U.S. coastline expected to see three to four times as many high-tide flood days each year for at least a decade.

The study, published June 21 in the journal Nature Climate Change, warns that these extra flood days won't be spread out evenly over the year, but are likely to cluster together over the span of just a few months; coastal areas that now face just two or three floods a month may soon face a dozen or more.

These prolonged coastal flood seasons will cause major disruptions to lives and livelihoods if communities don't start planning for them now, the researchers cautioned.

"It's the accumulated effect over time that will have an impact," lead study author Phil Thompson, an assistant professor at the University of Hawaii, said in a statement. "If it floods 10 or 15 times a month, a business can't keep operating with its parking lot under water. People lose their jobs because they can't get to work. Seeping cesspools become a public health issue."

Several factors drive this predicted increase in flood days.

For one, there's sea level rise. As global warming heats up the atmosphere, glacial ice is melting at a record pace, dumping enormous amounts of meltwater into the ocean. As a result, global average sea levels have risen about 8 to 9 inches (21 to 24 centimeters) since 1880, with about a third of that occurring in just the last 25 years, according to NOAA. By the year 2100, sea levels could rise anywhere from 12 inches (0.3 m) to 8.2 feet (2.5 m) above where they were in 2000, depending on how well humans restrict greenhouse gas emissions in the coming decades.

While rising sea levels alone will increase the frequency of high-tide floods, they will have a little help from the cosmos — specifically, the moon.

The moon influences the tides, but the power of the moon's pull isn't equal from year to year; the moon actually has a "wobble" in its orbit, slightly altering its position relative to Earth on a rhythmic 18.6-year cycle. For half of the cycle, the moon suppresses tides on Earth, resulting in lower high tides and higher low tides. For the other half of the cycle, tides are amplified, with higher high tides and lower low tides, according to NASA.

We are currently in the tide-amplifying part of the cycle; the next tide-amplifying cycle begins in the mid-2030s; — and, by then, global sea levels will have risen enough to make those higher-than-normal high tides particularly troublesome, the researchers found.

Through the combined effect of sea-level rise and the lunar cycle, high-tide flooding will increase rapidly across the entire U.S. coast, the team wrote. In a little more than a decade, high-tide flooding will transition "from a regional issue to a national issue with a majority of U.S. coastlines being affected," the authors wrote. Other elements of the climate cycle, like El Niño events, will cause these flood days to cluster in certain parts of the year, resulting in entire months of unrelenting coastal flooding.

Scary as this pattern sounds, it is also important to understand for planning purposes, the authors wrote.

"Understanding that all your events are clustered in a particular month, or you might have more severe flooding in the second half of a year than the first — that's useful information," study co-author Ben Hamlington of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory said in the statement.

Extreme weather events may get all the national media attention as they batter America's coasts, but high-tide flooding will soon be impossible to ignore. Best to start planning for it now, before it's too late, the authors concluded.

Extreme weather events may get all the national media attention as they batter America's coasts, but high-tide flooding will soon be impossible to ignore. Best to start planning for it now, before it's too late, the authors concluded.